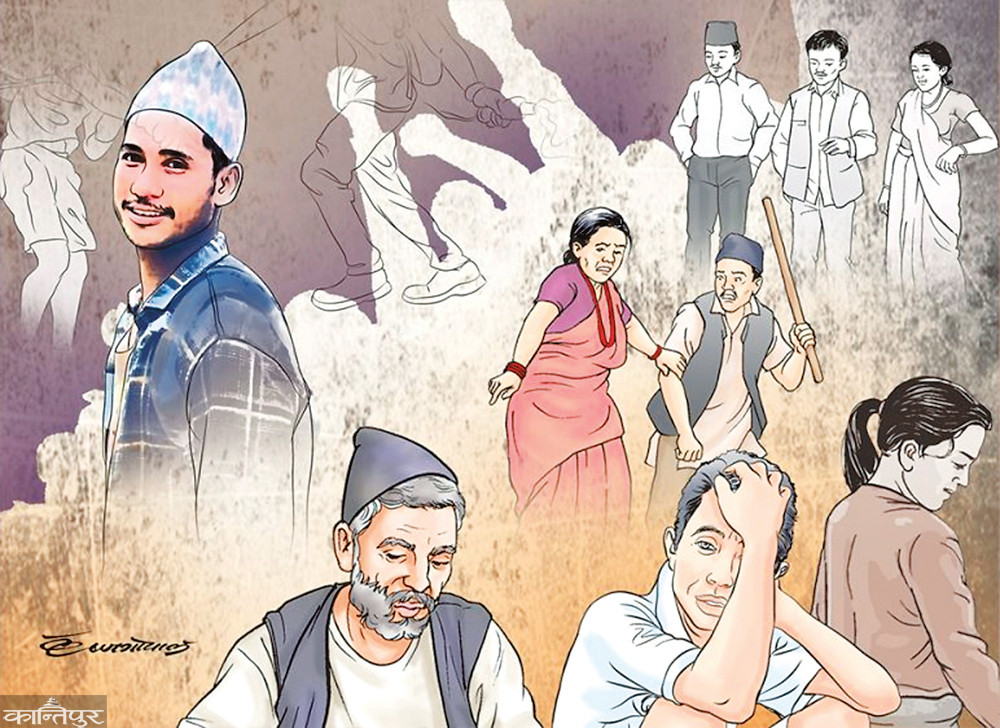

In May 2020, Nabaraj BK, of Jajarkot, a midwestern hill district in Nepal, had gone to the neighbouring district of Rukum (West) with a group of friends.

Nabaraj, 23, was in love with a girl from Rukum (West). He wanted to meet the girl and get married. But as soon as the group of young men reached the village, the girl’s family and relatives took Nabaraj under control. They lynched Nabaraj and his five friends and dumped their bodies into the Bheri river on the night of May 23.

The girl’s family and relatives were not happy that Nabaraj was a Dalit. The girl belonged to a so-called upper caste.

The trial for the Rukum (West) mass murder is still underway, more than a year since the incident. The families of the victims are getting increasingly worried if justice will ever be delivered.

To create pressure to fast-track the case, Nabaraj's relatives had recently visited Kathmandu with some uncomfortable questions: "Should we do to the culprits what they have done to Nabaraj? Is this what the state wants us to do?"

The Rukum (West) tragedy cannot be undone now, but timely justice could have perhaps redressed the wrong done to Nabaraj and his family, as well as to his five friends and their families.

Dalits in Nepal have suffered for generations at the hands of so-called upper-caste people and they continue to face atrocities even in today’s day and age. Caste-based discrimination is still rife in Nepal even after efforts—and the legislation—to end it.

The lynching incident in Rukum (West) took place exactly nine years after the legislature passed the Bill on Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability.

On May 24, 2011, the Bill on Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability, designed to end discriminatory practices aimed at those considered to be members of the Dalit community, was passed by Nepal’s legislature. The legislation prohibits any discrimination against anyone based on caste and treatment of any individuals as Dalits.

What complicated the Rukum (West) case further was its swift politicisation.

Several national and local political leaders threw their weight behind those accused of murdering Nabaraj and his five friends at Soti village in Chaurjahari Municipality-8 of the district. In an attempt to get the accused off the hook, Janardan Sharma, a lawmaker from the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre), manipulated the facts while addressing Parliament.

Sharma is currently finance minister in the Sher Bahadur Deuba government.

Not only did Sharma dismiss the fact that Nabaraj and his friends were lynched, he also claimed that they had died after jumping into the Bheri river.

Sharma was elected to Parliament from Rukum (West).

One of the main accused in the Rukum (West) lynching is Dambar Malla, a ward chair of Chaurjahari Municipality and is affiliated to Sharma’s party. Apart from Sharma, Chaurjahari Municipality's Mayor Bishal Sharma and Gopal Sharma, a member of Karnali Provincial Assembly, also actively lobbied for Malla's release. The Sharma duo has strong political links with top leaders in Kathmandu, and one of them, Mayor Sharma, is also a relative of Malla.

Krishna Khanal, a political scientist, says caste-based discrimination is not just a legal issue.

“It is a reflection of discriminatory social structure and practices. The courts may provide justice to some victims in some individual cases, but that does not end the systemic injustice Dalits are facing,” said Khanal.

“To end this injustice, political parties need to make strong and progressive interventions to uproot the main causes of untouchability. But today's political parties and leaders are not driven towards it. They have not been honest about their own causes.”

Dalit activists and rights defenders say Nabaraj’s is not an isolated case. Dalits are discriminated against in every part of the country, and caste discrimantion is rife even in Kathmandu, Nepal’s federal capital.

A case of caste-based discrimination in Kathmandu made headlines in June-July this year.

Rupa Sunar, a journalist, had visited the house of Saraswati Pradhan, a resident of Babarmahal in Kathmandu, looking for a flat to rent. Pradhan initially agreed to rent out the flat, but she backtracked upon learning that Rupa was a Dalit. Rupa lodged a police complaint against Pradhan for discriminating against her on the basis of her caste. Pradhan was arrested on June 20.

Once again, the case quickly became political. Krishna Gopal Shrestha, a CPN-UML leader, who was education minister then, went to the police office to receive Pradhan when she was released. Shrestha escorted Pradhan to her house in his official vehicle.

A minister’s act of siding with a person accused of caste-based discrimination was viewed as an attempt to influence police investigation, and he was heavily criticised in the press and social media. UML chair KP Sharma Oli, who was then prime minister, made a public statement: "I warn all to not discriminate against anyone on the basis of their caste, and to not protect anyone who is accused of committing such crimes."

Oli, however, did not take action against Shrestha.

"If the prime minister was genuinely concerned, he should have removed Shrestha from his ministerial post," said Shyam Bishwakarma, an advocate.

Rupa’s complaint against Pradhan was misinterpreted by some groups as a conspiracy to defame the Newar community.

"It was made out to be a Dalit versus Newar case,” said Bishwakarma. “It was a deliberate attempt to fuel caste-based discrimination."

Alarming statistics

Police data show that 63 Dalits have been murdered in eight districts of Province 2 in the last two years. But in most cases, the perpetrators have not been punished.

"Political interference is the main reason why most perpetrators get off the hook," said Bhola Paswan, an activist.

The number of cases related to caste-based discrimination has been on the rise over the years.

In the fiscal year 2019/20, a total of 49 cases of caste-based discrimination were registered at the National Human Rights Commission. During the first Covid-19 lockdown, as many as 753 cases of caste-based discrimination, including 34 murders of Dalits, were reported across the country. Most victims were women and children.

The annual report of the National Human Rights Commission for the fiscal year 2019/20 shows that 60 cases of human rights violations against Dalits were reported during the first lockdown. Most of these cases (31 percent) were related to caste-based discrimination, 20 percent about abuse of Dalits, 15 percent about murders of Dalits, 15 percent were related to hunger and 12 percent were related to Covid-19. Similarly, 7 percent cases were related to rape and murder of Dalit women and girls and 3 percent to abuse on social media.

In the fiscal year 2019/20, National Dalit Commission received 25 cases of caste-based discrimination. Most of these cases (32 percent) were related to caste-based discrimination and insult, 28 percent to physical assault on Dalits, and 16 percent to murder of Dalits for marrying non-Dalits. Likewise, 12 percent of the cases were related to violation of Dalit rights, 8 percent to social discrimination, rape and murder, and 4 percent were related to threats to a Dalit settlement.

According to Samata Foundation, a non-governmental organisation working for Dalit rights, 18 Dalits have been murdered because of their caste within the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. In the same period, 27 Dalits have been beaten because of their caste, 14 Dalit women have been raped, three Dalit women suffered attempted rape, seven have faced abuse for marrying non-Dalits, two others have been abused because of their love affairs with non-Dalits, and one woman was forced to abort her child. Six were forced to commit suicide.

"Some argue that caste-based discrimination has declined in urban areas, which is totally false. Discrimination has not decreased; it has only changed its form," said Bishwa Bhakta Dulal, who goes by one name Aahuti, a public intellectual and writer.

Political interference in investigation

Yamkala Acharya of Mai Municipality-2 in Ilam district could not pay final tributes to her father last year. She has been ostracised by her family for the last 12 years. Her 'crime' was marrying Ratna Bahadur Bishwakarma, a Dalit.

"When I heard that my father had passed away, I wanted to attend his funeral rites. But I was not allowed to even step onto the front yard of the house where I was born," says Acharya.

Acharya lodged a complaint against her brother Tikaram Acharya, Parbati Acharya and neighbour Laxmi Dangal. Police arrested them on the charge of discriminating against Acharya.

But Acharya's maternal aunt Bishnu Maya Rimal, deputy mayor of Mai Municipality, used her political clout to dismiss the case, she said. Elected on a ticket from the CPN-UML, Rimal is also the coordinator of the judicial committee of Mai Municipality.

"My aunt is a communist, and her political ideology opposes caste-based discrimination. But she is the one who discriminated against me," said Acharya.

According to Acharya, she was pressured to withdraw the case by Rimal and other local political leaders.

"Even those who spoke in my favour were threatened," she said.

Eventually, the District Court of Ilam released the accused on Rs15,000 bail each.

Dalits face discrimination not just when they are alive, but also after their death. Sambar Bahadur Sunar is an example.

A resident of Pokhara Ward 16, Sambar died while working abroad. His body was sent back home in a coffin. When his body was taken to a local cremation site for funeral rites, local Chhetri people were up in arms. They created obstacles in Sambar's exequies saying it was their cremation site, and Dalits could not be cremated there.

On April 26, 2020, Sambar Bahadur's family lodged a police complaint against those who obstructed his funeral rites. Police, however, refused to register the complaint under pressure from local political leaders, including a Provincial Assembly member of Gandaki elected for the UML. Police registered the case only after an instruction from the National Human Rights Commission.

An indifferent state

According to the Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability (Offence and Punishment) Act, 2011, a person found guilty of even insinuating that someone is from a “lower caste” can face three years of imprisonment, or a fine of up to Rs 25,000. However, in a country with such a progressive law against caste-based discrimination, Dalits are not only facing abuse due to their caste but are also being killed. Most Dalits are economically deprived and lack political connections, so they do not get justice even when their family members are killed. Political parties and leaders themselves protect those accused of discriminating against Dalits based on their caste.

"As long as we hope that caste-based discrimination will go away gradually, Dalits will continue to be subjected to this crime," said Pradip Pariyar, executive director of the Samata Foundation. “The state apparatus is often unwilling to investigate caste-based discrimination and punish the guilty in most cases, and Dalits often have to launch protests for justice.”

Advocate Prakash Nepali said it is always difficult to gather enough evidence in cases of caste-based discrimination.

"Most victims do not get justice because they are unable to gather evidence," he said. "So the law needs to be amended to lift this burden of proof off the victims. When someone is charged with caste-based discrimination, it should be their responsibility to prove otherwise. Also, the guilty should be jailed for up to five years."

According to the Samata Foundation, in the decade after the enactment of the Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability (Offence and Punishment) Act, 2011, as many as 91 hearings on cases of caste-based discrimination have been concluded by various district courts and the accused have got clean chits in 88 cases.

"What this means is that Dalits do not get justice in most cases," said Nepali.

Man Bahadur BK, a former government secretary, said the law against caste-based discrimination has not encouraged Dalits to seek legal remedy. In the first 10 years of the law, only 340 cases of caste-based discrimination were registered in courts.

"The law has not been effective in delivering justice to Dalits," he said.

In most cases, victims are afraid to file cases in courts fearing repercussions and recrimination. Dalit rights activists say police are unwilling to register complaints in most cases, which deters the victims from fighting for justice. Victims face abuse, threats and even social alienation when they seek justice, which stops many from going to courts.

"Even after the victims have lodged police complaints, they face pressure to reconcile with their abusers,” said BK, the former secretary. “Caste-based discrimination is a punishable offence, and there should be no room for reconciliation in such cases."

Activists say Nepal’s political parties have done next to nothing when it comes to fighting against caste-based discrimination. Political parties are dominated by non-Dalits, especially the so-called upper-caste people, according to them.

Parties often influence the investigation of criminal cases related to caste-based discrimination to protect the accused, especially those so-called upper-caste people who have personal and political links with them. So most of the accused never get punished, and the victims continue to face injustice.

Min Bishwakarma, a former minister and Nepali Congress leader, says caste-based discrimination was an important agenda during the first convention of his party, which took place in Janakpur in 1952.

In that convention, the Nepali Congress passed a resolution to abolish caste-based discrimination and fight against any force that perpetuates injustice. The party also circulated its stance about untouchability and caste-based discrimination to its district committees.

"Unfortunately, many leaders of our party not only approve of untouchability but also do not hesitate to protect those accused of caste-based discrimination," said Bishwakarma, who was a member of the drafting committee of the 2007 Interim Constitution.

Communists are no better, say activists and analysts.

According to political scientist Khanal, political parties should have introduced strong and progressive policies to end caste-based discrimination when they were most powerful and popular.

“Nepali Congress could have done it in 1990. The CPN-UML could have done so when their popularity rating was at an all-time high during their nine-month rule. The Maoists could have done it when they were the most powerful political force after the 2006 peace accord,” said Khanal. “But they all failed to end caste-based discrimination once and for all.”

Khanal also finds fault with the judiciary.

“A few justices and judges might be progressive about the caste system, but the overall system of judiciary is conservative,” said Khanal. “Those who are at the helm of police and other administrations are also conservative, when it comes to caste and caste-based discrimination.”

Rajendra Maharjan, an author and political analyst, stresses the need for a strong civic movement.

“Political parties were expected to deal with caste-based discrimination as a political agenda, but they are instead politicising criminal cases related to it,” said Maharjan. “Dalit organisations have also reduced themselves to puppets of political parties. Without order, instruction or hints from their political masters, these Dalit organisations do not issue a statement even on a public issue.”

According to Maharjan, only if Dalit organisations free themselves from calculative political parties and spearhead a movement in collaboration with non-Dalit communities, can they turn their issues into a political agenda for their emancipation.

“Political parties continue to busy themselves with power-sharing games unless they face powerful resistance from civil society groups,” said Maharjan. “There is no alternative to a strong civic movement to check-mate political parties, ensure justice for the victims of caste-based discrimination, and practically abolish this systemic injustice.”

Devraj Bishwakarma, chair of the National Dalit Commission, stresses the need for making the law against caste-based discrimination more stringent.

"For many in the law-enforcement agencies, caste-based discrimination is normal,” he said, adding, “So they do not act with sincerity to deliver justice to the victims."

(In collaboration with The Kathmandu Post.)